Caves and The Tsunami

I woke up in the car park next to the caves at around 9 this morning. Being so remote, it had been pitch black the night before, and I kept hearing all sorts of strange sounds coming from the forest. I didn’t sleep all that well – mostly psyching myself out, convinced a bear was going to come charging out of the treeline at any moment. Needless to say, I was absolutely fine once the sun came up.

The limestone caves were pretty amazing, to be honest. There were three larger chambers with smaller corridors connecting them, filled with stalactites and stalagmites all over the place. They were discovered in 1969 but apparently formed over 80 million years ago – quite impressive, really. I’m not the biggest fan of bats, but to my relief there were only a few in the larger caverns – a much better experience than the caves in Thailand, which were teeming with the little sods and left me mildly traumatised.

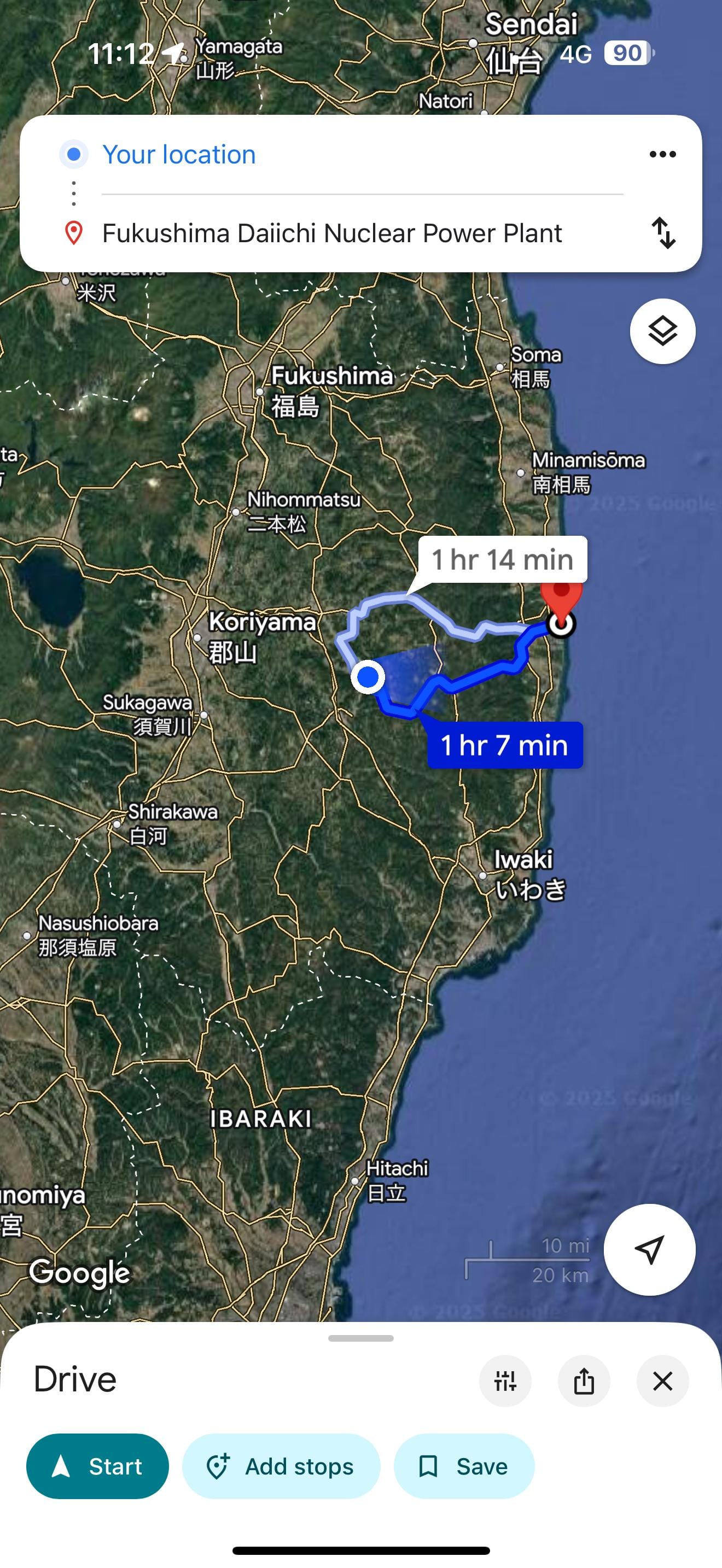

Once back on the surface, I headed to the car and set off towards the museum. I wasn’t really sure what to expect – until just a few years ago, the entire area I was heading into was closed off due to radiation fallout from Fukushima. I’d done a bit of Googling, but I wasn’t sure how far I’d actually be allowed to go.

I have to say, the drive through the mountains to the coast – despite the pouring rain – was one of the most beautiful yet. It was misty and surreal, winding through valleys filled with cherry blossom that, until 2017, were deemed too radioactive for human habitation.

About 15 minutes from the site of the explosion in 2011, I thought it wise to put the AC on recycle and double-check the windows were shut. Ten minutes out, I started noticing more and more signs with red lettering – still in Japanese, of course, so I had no idea what they said. Presumably warnings, but I carried on regardless. Five minutes from the site, I passed a Geiger counter mounted on an overhead gantry, displaying 1.139 mSv/h – which, as I found out later, is roughly equivalent to receiving 20 chest X-rays per hour.

I turned down a side road leading to the reactors and pulled up at a checkpoint where cars were stopping, seemingly to show some sort of permit – which, obviously, I didn’t have. I rolled up to the radiation suit-clad staff at the gate and gave them my best Japanese apology, followed by a hopeful “U-turn ikimasu”. Much to my surprise, they understood and let me turn around – though they did take down my number plate and rolled out a spiked barrier to make sure I wasn’t about to bolt towards the plant.

I passed the Geiger counter again – now reading slightly lower at 1.119 mSv/h – and continued a bit further north to the new museum, where all the radioactive topsoil has been removed. Much to my relief, the radiation here was only 0.062mSv/h so back down to what you’d normally expect.

The museum itself was really well done – honestly, I’d recommend visiting if you’re in Japan and interested in this kind of thing. It explained the history and culture of the region leading up to the tsunami and disaster, as well as the plans for rebuilding and reconstruction over the next 30 years. It wasn’t as critical of TEPCO (the company that managed the plant at the time) as some other sources I’ve read – the emphasis was more on the strength of the earthquake, rather than a failure to prepare for a tsunami. That said, the infamous Japanese bureaucracy and stove-piping of information definitely contributed to the disaster being as bad as it was. If you want to read more about it, I’d highly recommend the book Bending Adversity.

After leaving the museum, I headed to the still-standing Ukedo Elementary School – one of the few buildings that close to the coast not to have been washed away by the 15-metre wave. It’s been left standing over the years as a reminder of the scale of the damage. While the building is rusting now, you can still see the gym floor twisted and torn by the force of the quake. I walked from the school to the nearby sea wall and climbed up to have a look – it was a humbling experience, especially with the sea as rough as it was today.

The quake was the largest ever recorded in Japan’s history, at a magnitude of 9.0. The tsunami reached a peak of 40 metres high, affected nearly 2,000 km of coastline, and travelled up to 10 km inland. The official death toll, including those confirmed dead and those still missing, stands at around 18,500 – though some estimates put it at over 20,000.

Inside the largest cavern

Better safe than sorry

Hard to see in the video but the overhead Geiger counters are real

The height of the wave, marked on the second floor of the school building